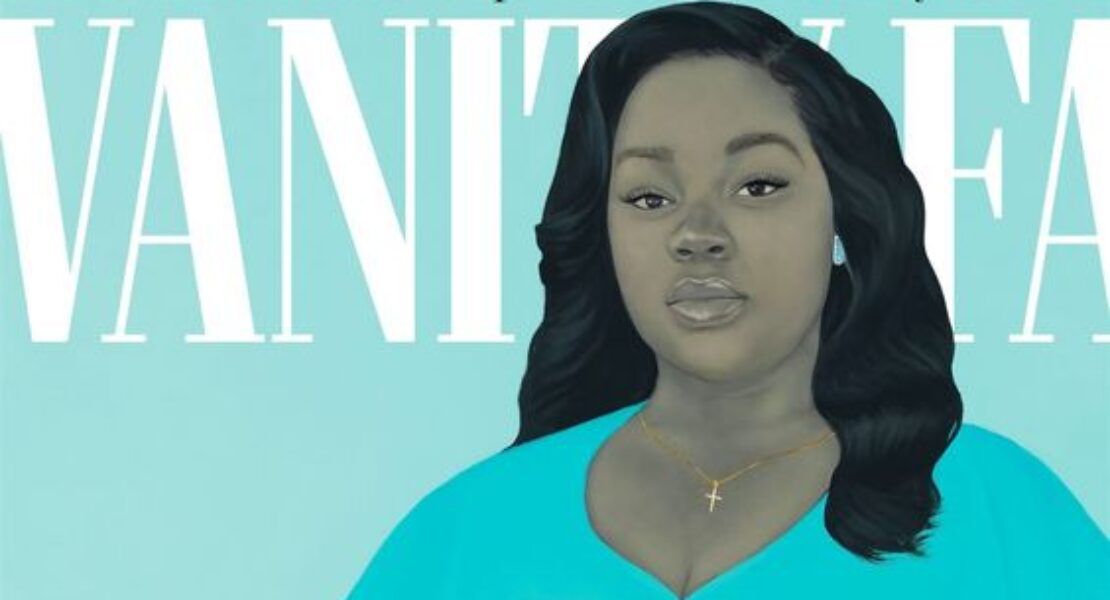

Vanity Fair magazine’s September cover features a new work by painter Amy Sherald: a bold portrait of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman who was fatally shot by Louisville Metro police officers in her home on March 13th, 2020. The cover graces a special issue, called “The Great Fire,” which includes contributions on the subject of systemic racism in the United States by independent curator and writer Kimberly Drew, and writer Kiese Makeba Laymon, among others. Guest edited by award-winning author Ta-Nehisi Coates, the issue also features a series of interviews with Tamika Palmer, Taylor’s mother, and intimate photographs of Taylor’s family taken by LaToya Ruby Frazier.

Sherald gained international recognition when she painted former United States First Lady Michelle Obama for the National Portrait Gallery in 2018. She is best known for her figurative paintings of individuals dressed in brilliantly colored clothing, with gray-scale skin tones. In Sherald’s portrait, Taylor is shown in the artist’s signature gray tone against a light aqua blue background. Taylor stands with her right hand placed on her hip and her gaze fixed straight ahead. She wears a flowing dress, which is just a fews shades darker than the hue of the background.

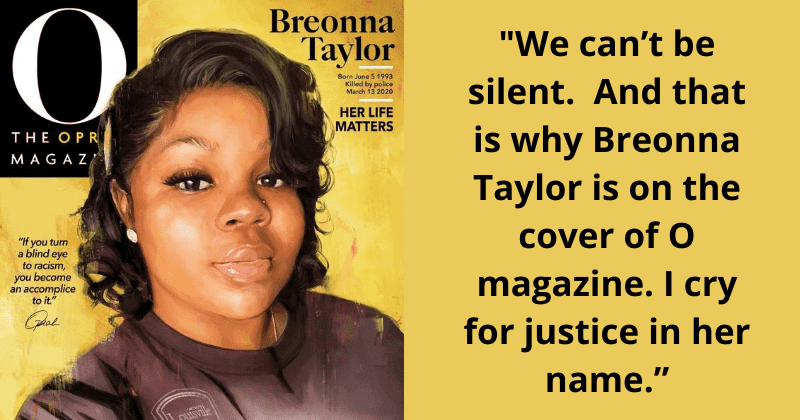

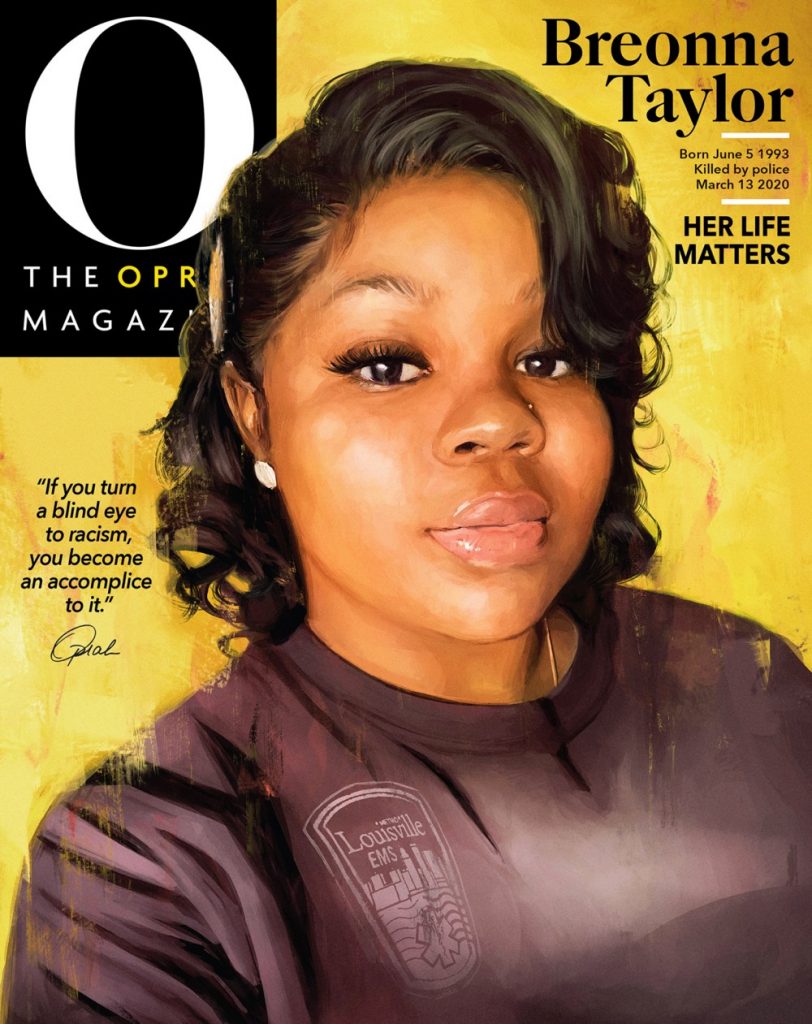

For the first time in its 20-year existence, Oprah Winfrey is not on the cover of her eponymous magazine. The media mogul has ceded the space to the late Breonna Taylor, asking readers to join the calls for justice for the 26-year-old emergency medical technician, who has become an iconic catalyst for artists all over the world.

The artist behind the cover art, which is based on a widely disseminated selfie of Taylor, is Alexis Franklin, a 24-year-old Black woman who works primarily as a church videographer. Self-trained, Franklin was determined to capture Taylor’s spirit in the portrait.

“There was a sparkle in Breonna’s eyes—a young Black woman posing in her Louisville EMS shirt, happy to be alive,” she wrote in Oprah magazine. “So many things were going through my mind—Breonna’s life, mostly, and how it ended so abruptly and unnecessarily. Every stroke was building a person: each eyelash, each wisp of hair, the shine on her lips, the highlight on her cheek.”

Franklin’s other high-profile projects include honoring Anita Hill for TIME magazine’s 100 Women of the Year project, celebrating the achievements of women over the past century. (The publication retroactively selected Hill as Woman of the Year for 1991 in recognition in her testimony against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.)

Franklin gained attention through her wildly popular Instagram account, where she shares photos of her finished digital portraits (as well as progress shots on her stories) with her 123,000 followers.

By any metric of success, Taylor’s family have gotten their wish: Their calls to keep Breonna Taylor’s name alive have been heeded. Along with the beautiful portraits of a infamous face.

But alongside the prominent spread of “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor,”we have a new, perplexing quandary. On social media, regardless of intent, her supporters often seem to blunt the impact of their message by treating phrases like “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” and “it’s a great day to arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” almost as a punch line. But her image is often reinterpreted by artists from all walks of life because we all know this woman. She’s our neighbor, our colleague, our chit-chat girl, our BAE, and now our Mona Lisa.

Many people want to believe we live in a society in which all possess the same rights as others. But they must disabuse themselves of the belief that the violence directed at Ms. Taylor—and the (initial) bureaucratic nonresponse—is exceptional. In reality, racialized violence is a constitutive structure of our society. Once you understand that, you can discover what really happened to Breonna Taylor and why her image will forever be iconic.